- awesome MLSS Newsletter

- Posts

- Learning as a function of learning as a function of learning as a.... - Awesome MLSS Newsletter

Learning as a function of learning as a function of learning as a.... - Awesome MLSS Newsletter

12th Edition

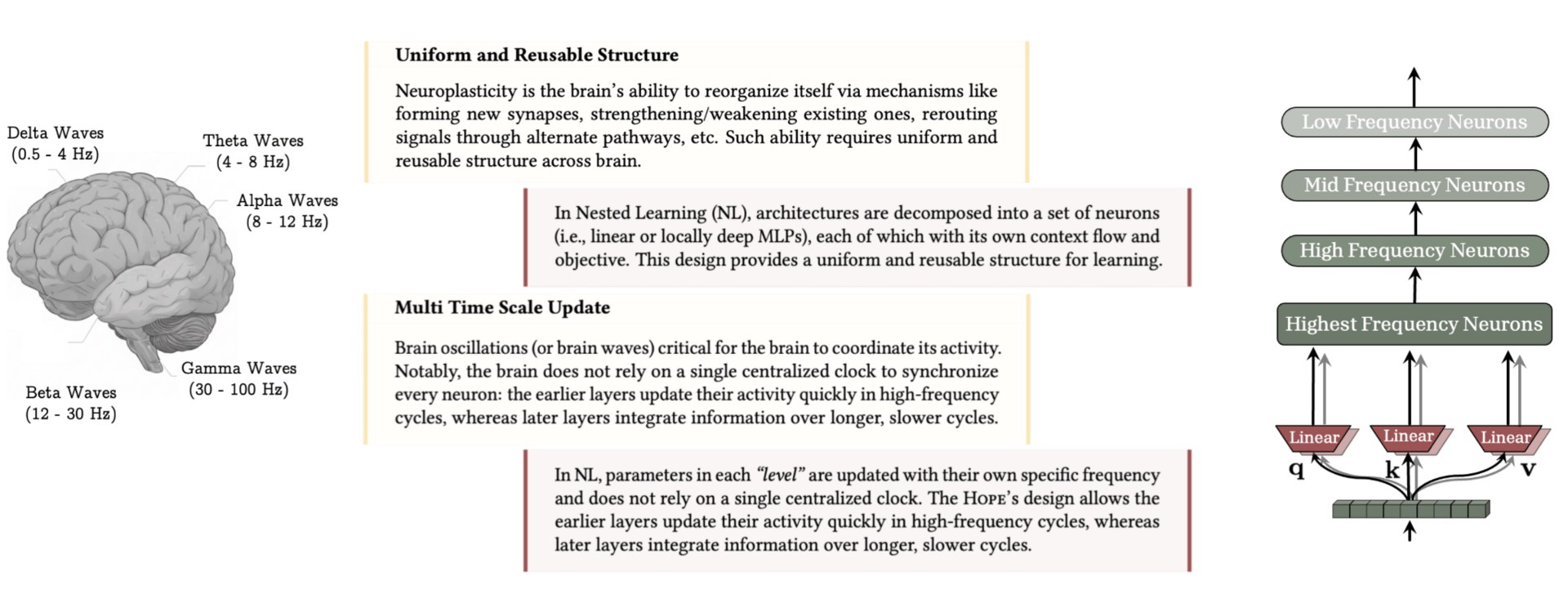

In July, we wrote about why it’s good to be plastic, exploring neural architectures inspired by biological brains. For years, researchers have aimed to make artificial networks more brain-like, enabling test-time memorisation and faster, more continuous learning. Recently, Google introduced a new paradigm called Nested Learning, which models networks as learning, memorising, and operating at different rates—a concept grounded in a strong theoretical framework.

The human brain doesn’t work like a neural network. Even if it resembled a transformer, different brain regions operate at different frequencies, from Alpha (8–12 Hz) to Gamma (30–100 Hz). Faster waves handle immediate memory, sensory input, and active thinking, while slower waves like Delta and Theta support long-term memory and learning.

There are two limitations to the current architectures and pipelines - the first, current architectures do not fully support continuous learning, it can be expensive to finetune repeatedly, and second, the issue of catastrophic forgetting persists, as anyone who has finetuned a model would understand. This paper highlights how both these problems can be solved with their new architecture.

The paper in itself provides the complete mathematical basis, so for those interested, we strongly recommend that you read it in detail. For the purpose of this newsletter, we will be focusing more on the intuition behind the theory

Associative Memory

Consider training a single linear layer. During backpropagation, a loss function measures error and updates weights to better match the target distribution.

But this produces a static network: once training ends, weights can’t adapt at test time, limiting continual learning. This is an issue for continual learning, since we want to be able to update the network on a regular basis.

The authors argue that in fact, the weights of the neural network could be considered an associative memory, one that maps the outputs of the neural network closer to the data distribution.

They reformulate training so weight updates are driven by an associative memory—the momentum term—updated via gradient descent. This creates a two-level memory system: momentum captures short-term, high-frequency gradient information, while the weights store long-term, low-frequency knowledge.

Example with Attention

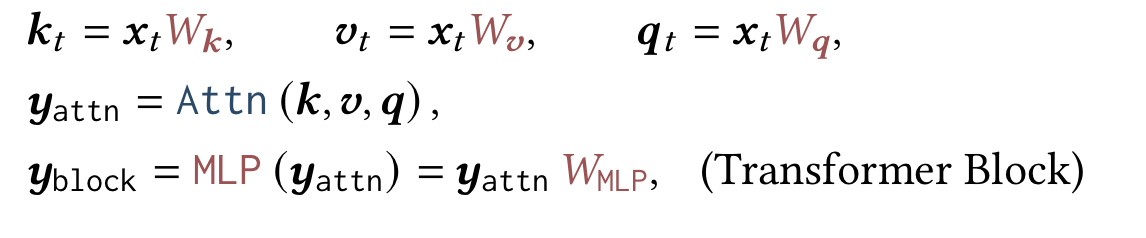

Consider the humble transformer. We all know the attention formula, wherein we use three learned weights, Wk, Wv and Wq, manipulate them via a formula, and pass it through a linear layer (assume no normalisation for simplicity)

Image Credits: Nested Learning Paper

In this case, we can view the weights Wk, Wv and Wq as slow learning memory (red font) that update only during backpropagation, while the attention layer can be seen as fast learning memory (blue font), updating at each time step, even during inference. So transformers ALREADY form a multi-level associative memory system.

Optimisers as Associative Memory

The researchers also note that given two neural networks, if all other variables were held constant (data, batch size, learning rates etc.) the choice of optimiser actually changes the output considerably. An LLM trained on Adam vs. one trained with stochastic gradient descent will spout different words even when trained with everything else kept constant.

Coming back to the argument regarding how weights themselves are an associative memory between expected and correct outputs, the authors argue the optimiser also acts as an associative memory, teaching the network to map the memories in a specific manner.

While this may seem less relevant in today’s pipelines where weights are static after deployment, it is critical for continual learning, where new memories must be continuously integrated with past learning. The authors therefore reformulate momentum-based optimizers with gradient preconditioning such as Muon, which projects gradients into an orthogonal space to better separate tasks and rewrite the updates as projections into an associative memory space. They call the resulting optimizer Multi-scale Momentum Muon (M3).

Why is this important?

In continual learning, catastrophic forgetting is unacceptable: fine-tuning transformers often causes them to lose past tasks. By treating the network as an associative memory and mapping gradients orthogonally, past knowledge can be preserved while new learning is added.

While backpropagatioņ itself can be viewed as an associative memory, it lacks the expressivity needed to retain sufficient information about past learning. Momentum-based methods improve this but still tend to lose information over time. The authors therefore explore more expressive alternatives, detailed mathematically in Section 4 of the paper.

Since optimizers are treated as associative memories, their updates must also encode past gradients. This formulation explicitly enables that.

Knowledge Transfer Between Levels

Neural networks are deeply connected at various levels. There is knowledge transfer occurring at both training and test time, either via parametric sharing, or via output sharing. This sharing can also occur between different frequencies of memories, such as in attention, where the slow moving memory (of Wk, Wq, Wv) are connected to fast moving memory (Attention layer), which is then again connected to slow moving memory (Feedforward network)

This ordered stacking of knowledge transfer in itself forms a composable block of associative memories, where the next layer of a transformer is deeply affected by the outputs of the prior layer, while internally within each layer, there is a set of associative memories as highlighted above

The authors discuss many modalities of such knowledge transfer, and formulate it, for which you may refer section 3.3 of the paper entitled Knowledge Transfer Between Levels

Continuum Memory System

Imagine a simple transformer network, with Layers L1 - L12 (in the general case, consider MLP layers). These form what the authors refer to as a continuum memory system, since there is continuous knowledge transfer and associative memory between each layer.

The authors then propose a new training mechanism, where each layer is trained at a different frequency, and formulate exhaustively what these methods could be. As a simple example, imagine that each layer i is only finetuned at timesteps t where i mod t = 0, and if i mod t != 0, the optimiser simply stores the information necessary for calculating gradient when it is required.

This way, L1 is updated every timestep, L2 once every two steps, so on, and L12 only once every 12 steps. How knowledge and gradient transfer occurs between them, is a design choice, discussed in section 7.1.

HOPE - A Self Referential Learning Module with Continuum Memory

The authors then propose HOPE, a new architecture which incorporates the above continuum memory system. However, do note that we still haven’t solved one problem - how does the continuum memory system remain flexible enough in updates to not make it expensive to retrain at each step, while still retaining past learning?

Deep Self Referential Titans

With the new formulations around optimisers (M3) and continuum memory systems, the authors reformulate attention mechanisms such that they depend entirely on memory, and not gradients. The parameters, which include the weights of the layers and the optimiser state, are updated only using memory, allowing them to be updated in context, and not just via gradients.

The memory is itself optimised with some form of optimisation, but it allows for retention of long term memory, while the parameters of the neural network can be updated in context using only the memory. Details are available in section 8.1

HOPE Neural Learning Module

The neural module consists of a deep self referential titan, followed by a continuum memory system. The authors also introduce HOPE-Attention, in which the self modifying titans are given softmax global attention. This neural module forms one single MLP block.

Image Source: Nested Learning Paper

Experimental Results

Using Llama-3-8B and Llama-3B as backbones, the authors integrate HOPE layers to enable adaptation and continual pre-training over 15B tokens, then evaluate the models on tasks requiring long-context understanding and in-context learning. Competing models were also fine-tuned on the same 15B tokens.

They find that more memory levels in HOPE improve performance, and lower slowest learning frequencies (e.g., updating the slowest module every 512 steps vs. 2048) further boost results—but at higher computational cost due to more frequent updates.

The authors frame pre-training as a form of in-context learning (ICL), where the context is the entire dataset. With all models pre-trained on the same data, they compare ICL against Continuum Memory Systems (CMS) for performance analysis.

Language Translation

In the first task, which was new language learning, across all levels of memory, CMS beat ICL. This was tested on two tasks, first only learning one language translation at a time (to serve as baseline for catastrophic forgetting), and the second task being learning all languages at the same time. The performance in the second task in particular showed serious performance drop in ICL, while CMS performed better

On Long Context Understanding

In the needle in a haystack experiments, the authors use a mix of different setups such as single needle but different types, multi key extraction, multi query extraction, etc.

Here, HOPE achieves best performance across all tasks and levels of difficulties. Especially compared to linear memory, deep memory modules have better capability with longer sequences owing to their ability to compress more tokens. Even against transformer networks, the HOPE-Attention module works better.

In the BABILong evaluations, HOPE is compared with more modern models such as GPT-4 and GPT 4o-mini, Llama-8B, and other SOTA small models trained exclusively for this task, apart from Titans.

Large models showed significant performance drop with increasing sequence length, failing around 128k-256k long context sizes. RAG augmented models also showed drops with increasing context size, stabilising post 256k length. Among finetuned models, Titans and others, HOPE shows competitive results until context length of 1M tokens, but beyond that, HOPE outperforms them all the way up to 10M tokens.

There are several other tests that were run, but it is difficult for us to exhaustively elaborate each result. We strongly recommend reading section 9 of the paper. However, overall, the results are generally positive, providing strong evidence in favour of the HOPE architecture and continuum memory systems.

HOPE and CMS present an entirely new way of thinking about systems, enabling more expressive designs and continuous learning. The authors do note that catastrophic forgetting is not yet ‘solved’, but has been greatly reduced. The improvements in long context understanding also show us that the notion of dumping several novels into a single inference step might yet be a possibility without loss of understanding by the model.

Awesome Machine Learning Summer Schools is a non-profit organisation that keeps you updated on ML Summer Schools and their deadlines. Simple as that.

Have any questions or doubts? Drop us an email! We would be more than happy to talk to you.

Reply